150 Years of Woods Hole Science

31

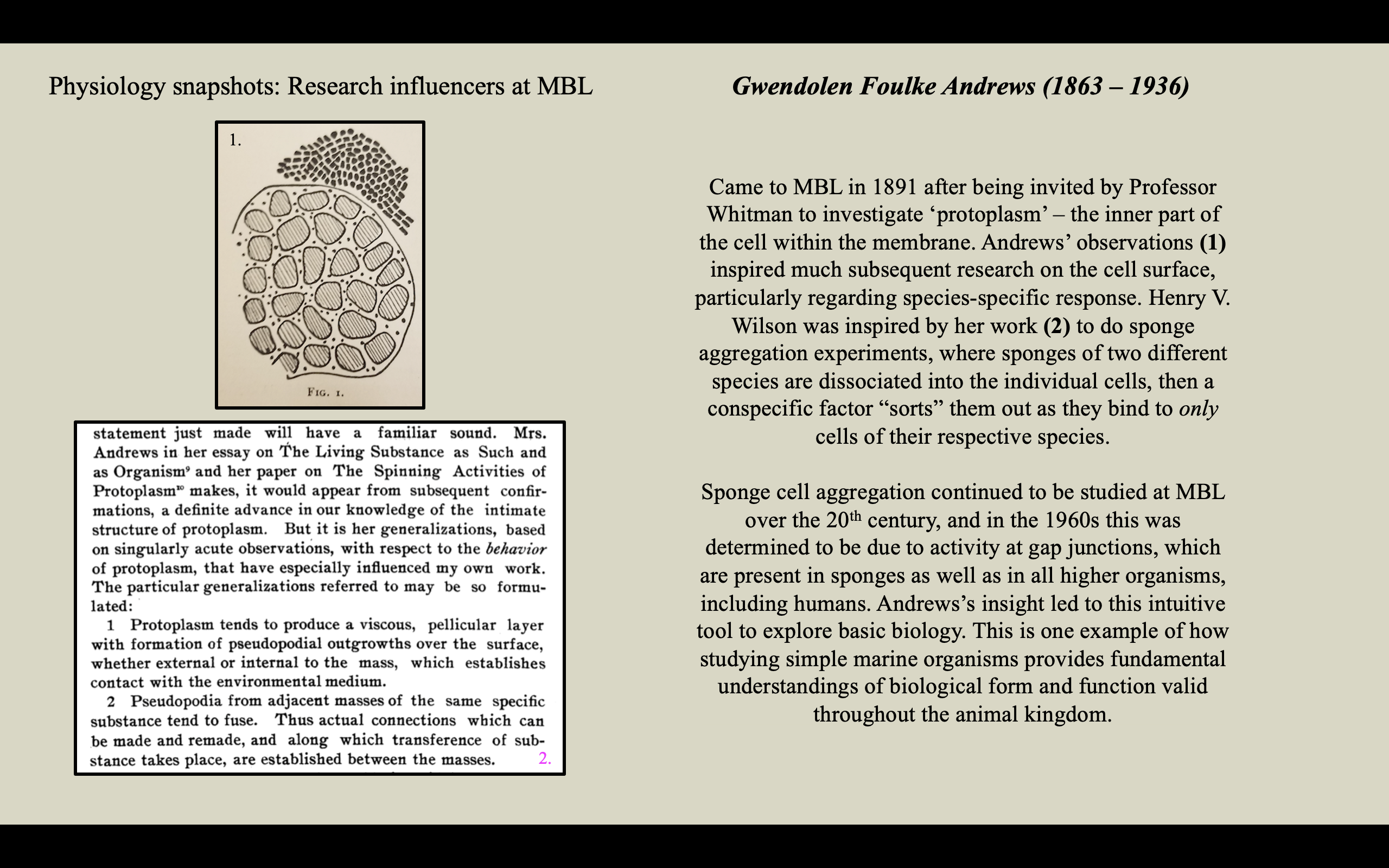

Fig 1: From Andrews, 1897b. Drawing representing her observations of “protoplasmic” characteristics.

Fig 2: from Wilson, 1907. Acknowledgement of Andrews’s work.

References:

Andrews, G.F., 1897a. Some spinning activities of protoplasm in starfish, and sea?urchin eggs. Journal of Morphology, 12(2), pp.367-389. Andrews, G.F., 1897b. The living substance as such: and as organism. Ginn & Company. – Fig 1.

Levin, M., 2012. Morphogenetic fields in embryogenesis, regeneration, and cancer: non-local control of complex patterning. Biosystems, 109(3), pp.243-261.

On the relevance of gap junctions in cell:cell communication and modern milestones of physiology and its relevance to morphology:

“…interruption of cell:cell communication via ions and other small molecules (gap junctional isolation) is known to be a tumor-promoting agent (Loewenstein, 1969, 1979, 1980; Loewenstein and Kanno, 1966; Mesnil et al., 2005; Rose et al., 1993; Yamasaki et al., 1995); for example, Connexin32-deficient mice have a 25-fold increased incidence of spontaneous liver tumors (Temme et al., 1997). Gap junction-mediated, bioelectrically-controlled cell:cell communication is also a critical system by which the large-scale left-right asymmetry of the heart and visceral organs is determined during embryogenesis (Chuang et al., 2007; Fukumoto et al., 2005).”

Wilson, H.V., 1907. On some phenomena of coalescence and regeneration in sponges. Journal of Experimental Zoology, 5(2), pp.245-258. – Fig 2.