150 Years of Woods Hole Science

29

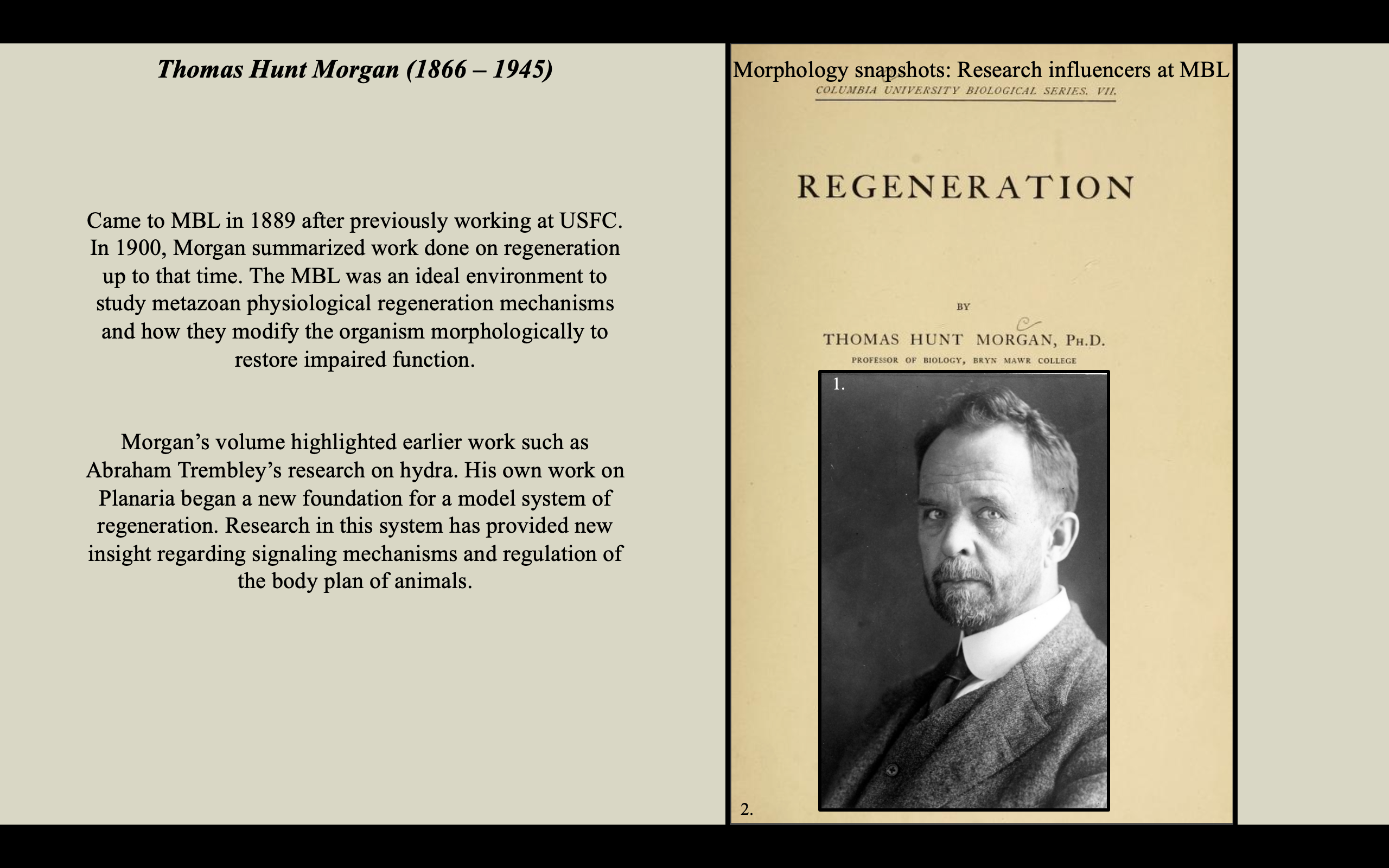

Fig 1: Thomas Hunt Morgan from Marine Biological Laboratory Archives https://hdl.handle.net/1912/20935

Fig 2: From Morgan, 1901.

References:

Levin, M., 2012. Morphogenetic fields in embryogenesis, regeneration, and cancer: non-local control of complex patterning. Biosystems, 109(3), pp.243-261.

On planarian regeneration and insight into signaling and regulation of the body plan:

“Physiological states of cells are crucial for determination of shape; it was recently shown that experimental control of transmembrane potentials can…reprogram the posterior-facing blastema in a fragment of the planarian flatworm to regenerate a head instead of a tail (Beane et al., 2011), reverse the left-right asymmetry of the internal organs in several species (Adams et al., 2006; Levin et al., 2002).

“In planaria, an amputated fragment always regenerates a head and tail at the appropriate ends. However, a brief (48-hour) isolation of cells from their neighbors via gap junction closure results in the formation of 2-headed worms. These worms will then continue to regenerate as 2-headed worms, even when cut in the absence of any other reagent! The transient, non-genotoxic perturbation of physiological networks active during regenerative repair permanently changed the pattern to which these animals regenerate after damage even in multiple rounds of amputation months after the initial treatment (Oviedo et al., 2010).

“starved planarian flatworms shrink allometrically – as the cell number is reduced, they dynamically remodel all of their tissues to retain perfect mathematical proportion among the various organs (Oviedo et al., 2003).

“Indeed some complex creatures (e.g., planaria) can regenerate the entire body (including their centralized brain) from a fragment of the original animal (Reddien and Sanchez Alvarado, 2004).

“…planarian flatworms in which physiological communication is transiently inhibited among cells have a permanent re-specification of body shape, regenerating as 2-headed “Push-me-pull-you” shapes when cut without any further manipulation (Oviedo et al., 2010)…These data suggest that the target morphology does indeed exist (and can be experimentally modified), since no “head organizer” remains when the 2-headed worm is cut into thirds – it appears that all regions of the animal have adopted the new shape to which the animal must repattern.

“Induction of anterior regeneration in planaria turns posterior infiltrating tumors into differentiated accessory organs such as the pharynx (Seilern-Aspang and Kratochwill, 1965), which suggests the presence of regulatory long-range signals that are initiated by large-scale regeneration.

“Anticipating recent discoveries of the importance of gap-junction cell:cell communication for planarian regenerative patterning (Nogi and Levin, 2005; Oviedo et al, 2010), in 1965 Seilern-Aspang described planarian experiments in which a carcinogen led to formation of many head teratomas with irregular nerves and un-oriented eyes saying “the cell-isolating action of the carcinogen prevents formation of a simgle morphogenetic field and leads to the establishment of several separated fields of reduced dimensions” (Seilern-Aspang and Kratochwill, 1965).

“In planaria, the integrity of the ventral nerve cord is actually required to specify appropriate fate for a regeneration blastema: if the VNC is cut in a gap junction-inhibited worm, an ectopic head can result (Oviedo et al., 2010).”

Maienschein, J., 2011. Regenerative medicine's historical roots in regeneration, transplantation, and translation. Developmental biology, 358(2), pp.278-284.

Morgan, T.H., 1901. Regeneration (No. 7). Macmillan.

Sturtevant, A.H., 1959. Thomas Hunt Morgan. Biographical Memoirs, National Academy of Sciences, 33, pp. 282-325.