150 Years of Woods Hole Science

6

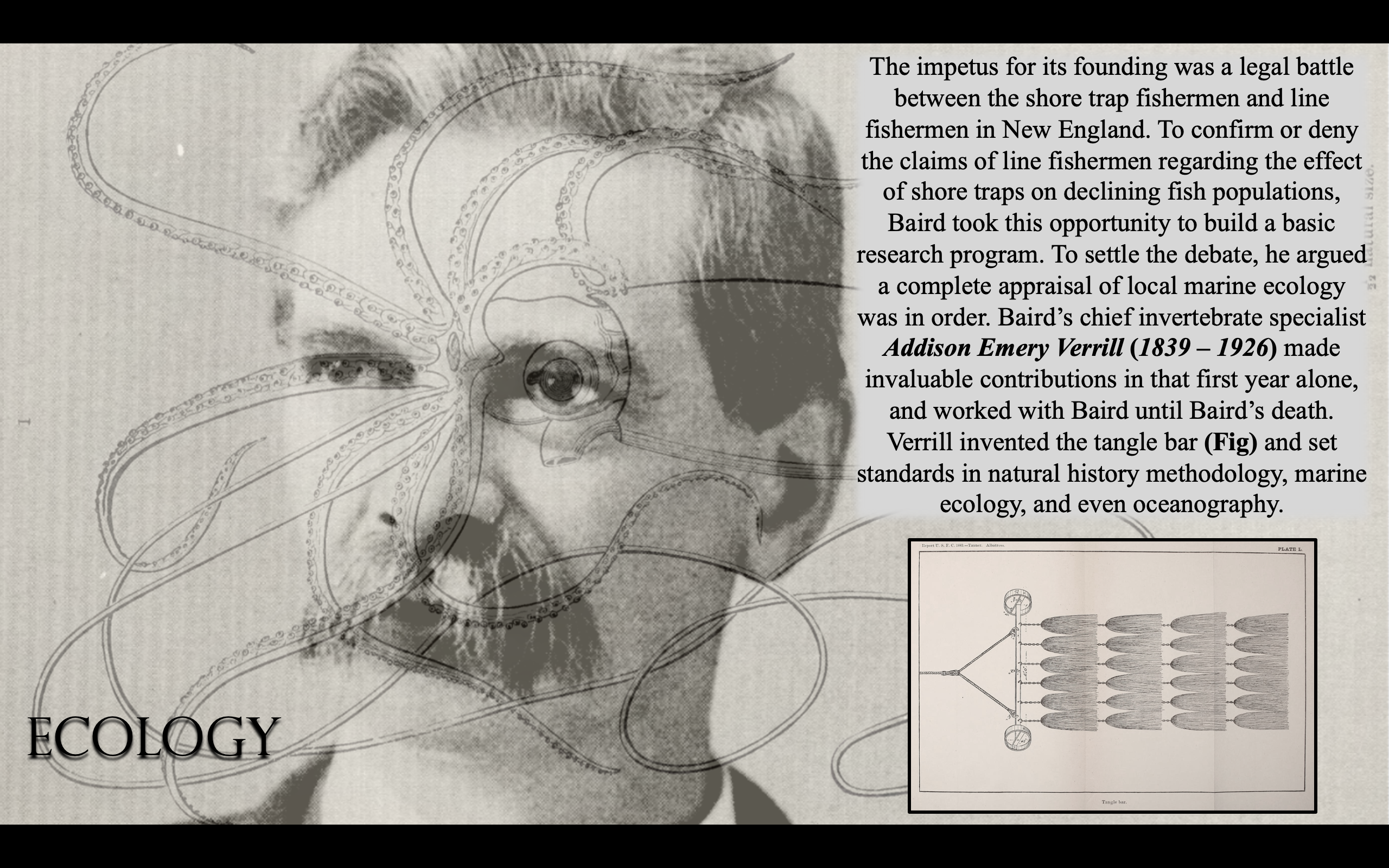

Fig: From Report, 1885 p. 112, Plate L: Tangle Bar. Verrill’s tangle bar for trawling uneven, rocky bottoms. Verrill invented many collecting tools while at the USFC, particularly for dredging, trawling, and sieving during collection.

Background image overlay: From Galtsoff, 1962, p. 14, Fig. 6: Addison E. Verrill, exploration of marine invertebrates at Woods Hole, 1871-1886. Credit: NOAA Fisheries. From NOAA archives gallery at https://apps-nefsc.fisheries.noaa.gov/rcb/photogallery/assorted.html

Background image: Report, 1882., p. 436, Plate II: Architeuthis harveyi- A restoration, 1/22 natural size, based on the preceding figures and on the specimens received.

References:

Allard Jr, D.C., 1967. SPENCER FULLERTON BAIRD AND THE UNITED STATES FISH COMMISSION: A STUDY IN THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN SCIENCE. The George Washington University.

p. 69:

“As Baird was working in Woods Hole during the summer of 1870 a dispute of considerable importance in southern New England was reaching a crisis. Essentially, this was a struggle between two types of property owners. On the one hand was a handful of men who owned fixed nets scattered along the shore that in the spring and early summer took enormous quantities of fish. These devices, sometimes stretching more than a thousand feet into the sea, were oi various designs. Some, made of boards or brush, were known as weirs. 0ther-;3, constructed of nets stretched around posts, were called pounds, fykes, or traps, depending on their configuration. Although these highly efficient instruments of capture were found along the entire coast between the tip of Cape Cod and Long Island, they were especially concentrated in certain areas. Two of these, Vineyard Sound and Buzzards Bay, were in the Woods Hole area. Bitterly opposed to these traps and to their owners was a much larger group that followed the age-old technique of fishing from small boats or the shore with single lines. Some of these men would have answered Samuel E. Morison's vivid description of the retired ocean fisherman who when rheumatic arms could no longer haul on sheet or cable, and eyes grew dim from straining through night, fog, or easterlies . . . retired from deep waters, and puttered about with lobstering, shore ”;

p. 70:

“…fishing, or clam-digging. Others had been prematurely forced out of other maritime trades due to the precipitous decline of the merchant marine and the whaling industry since the Civil War, and the steady concentration of blue-water fishing in the ports of Gloucester, Portsmouth, and Boston. Added to this group were mechanics and factory workers who supplemented their slim incomes with shore fishing. Finally, and somewhat incongruously, should be included the growing number of sports fishermen that flocked to the shores of New England for recreation. One New England state had already taken legal steps that apparently resolved the controversy over fixed nets. In Connecticut, traps concentrated at the mouth of the Connecticut River had been blamed by the line fishermen for preventing the shad from running up the river in the spring. In 1868, these protests led to a law regulating the nets for several years and then providing that after 1871 they would be absolutely barred.”

p. 71:

“But in the states of Rhode Island and Massachusetts, the dispute over fixed nets was just reaching a crisis in the summer of 1870.

p. 76:

“The immediate origin of the United States Commission of Fish and Fisheries lay in the impasse that had been reached by the fall of 1870 between the trap and anti-trap factions…As a representative of the federal government standing above local interests, Baird might be able to bring the states of southern New England into agreement on a regulatory policy. As a scientist, he could perhaps solve the mysteries surrounding the decline of coastal fishes by posing questions to nature itself, instead of to fishermen and other interested parties. So far as Baird personally was concerned, there were excellent reasons to look into the matter. He was keenly interested in proving the utilitarian value of science. And there were excellent opportunities for undertaking basic marine biological research in the process of undertaking practical work.”

p. 81:

“Baird's search for Congressional support was not without its price. To gain the votes of representatives from outside the New England region, Baird and Dawes found it best not to restrict the locality of the agency's work…A second major concession to politics was an agreement that the proposed organization would be headed by a civil officer of the government serving without additional pay.”

p. 85:

“On 7 February 1871, the day following Senate passage of the resolution, Edmunds took Baird to the White House for a personal interview with Grant. In the course of it, Baird was offered the post and he accepted. After quick approval by the Senate, Baird received his appointment on 8 March 1871.”

pp. 87-88:

“For the survey of the Vineyard Sound region, Baird chose Addison E. Verrill, professor of natural history at Yale and a former student of Louis Agassiz. Verrill first met Baird in 1860 when Agassiz sent him to Washington to raid Baird's collections for the new Museum of Comparative Zoology. But, despite this unpromising beginning, Verrill and Baird became good friends. Verrill was a shy, introverted scholar and a distinguished student of invertebrate marine animals. At Woods Hole, his chief practical assignment was to determine whether, as Nathaniel Atwood charged, a decline in mollusk beds was responsible for the diminution of coastal fishes. But, like Baird himself, Verrill also had broader scientific interests. His personal work at Woods Hole, as well as the achievements of his students and scientific friends, made clear early in the history of the Fish Commission that basic science was a prime concern.”

p. 89-90:

“These efforts focused on the solution of the difficult problems growing out of the dispute over traps in southern New England. But a closely related activity was general biological research in the Woods Hole area…One of the great contributions of Spencer Baird was the broad approach that he took to these problems. From the first, he refused to restrict his research to the important commercial fishes, even though it was their fate in which he was especially interested. This approach obviously supported Bairds broader goal of making a basic study of marine biology off the coasts of the United States. It also had validity for the practical goals with which he was charged, since to understand commercial species it was essential to study their total environment…The breadth of Bairds program was also seen in the specific aspects of the environment he elected to study. Not only was the Commissioner concerned with a systematic description of the organisms of the sea. He also studied the food of these organisms, their migrations, the impact of parasites and diseases, the influence of weather conditions, water temperature, salinity, and currents, and the role played by man through pollution or fishing. In the words of a modern fishery scientist, Bairds "broad philosophical approach to the major problems” of the fisheries is entirely recognizable to current investigators. His work combined oceanographical and meteorological investigations with the studies of biology, ecology, parasitology, and population dynamics of various fish species Baird*s program of research is as comprehensive and valid today as it was 90 years ago.”

pp. 91-92:

“Through dredges towed by the Commission’s boats or by shore collecting expeditions, Verrill determined the location of the mollusk beds in the area and attempted to ascertain whether they had actually declined, as Nathaniel Atwood charged. More than that, this part of the investigation measured the abundance of the small floating animals and plants composing the plankton. A knowledge of both the plankton and the mollusks was crucial for the practical task of studying the fish decline since it was clear that these were the major sources of food for most coastal species.”

pp. 100-101:

“Though Baird’s team failed to determine the cause of reduced numbers of scup, the conclusions alluded to the fact that more work needed to be done, and more basic knowledge of fish and marine ecology was necessary. “…the experience of the Fish Commission during its first year’s work showed that fisheries research offered exceedingly valuable scientific by-products…Baird made no secret of his basic scientific interests.”

p. 102:

”…little was known on the marine biology of America. Since “nearly all (other) enlightened nations have devoted much time” to its study it was high time for the United States to make an effort.”

Galtsoff, P.S., 1962. The story of the bureau of commercial fisheries, Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, Massachusetts (Vol. 145). US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Commercial Fisheries.

p. 14: Background Image

Report, 1873. U. S. Commission of Fish and Fish and Fisheries, Report of the Commissioner for 1871 and 1872, 1,

pp. XIII-XIV:

“…I (Baird) left Washington and established myself at Wood’s Hole, where shortly after my arrival I was joined by Mr. S. J. Smith and by Professor A. E. Verrill, of Yale College, who had kindly undertaken to conduct the inquiries into the invertebrate fauna of the waters. With the facilities in the way of steamers and of boats already referred to, I repeatedly visited in person the entire coast from Hyannis, Massachusetts, to Newport, Rhode Island, as well as the whole of Buzzard’s Bay, Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard, &c.”

pp. XIV-XV:

“…seines and nets of different kinds were set or drawn almost every day, for the purpose of ascertaining facts connected with the spawning of the fish, the rate of growth of the young, the localities preferred by them, &c. Professor Verrill and his parties were engaged also throughout the summer in making collections along the shores at low tide, as also in the constant use of the dredge and the towing-net. One important question connected with this investigation, in addition to determining the character of the food available for the fishes, was to ascertain its comparative abundance, a great diminution or failure of such food having been alleged as one cause of the decrease of fisheries. Care was therefore taken to mark out the position and extent of different beds of mussels, worms, star-fishes, &c., at the sea-bottom, and by straining the water at various depths and at the surface, to ascertain the amount of animal life therein. Temperature observations were also repeatedly taken and recorded, especially from the revenue-cutter Moccasin, under command of Captain Baker.”

p. XV:

“With a view of exhibiting the character of the fishes of the region explored, and determining their rate of growth, an experienced photographer accompanied the party, who, in the course of the summer, made over two hundred large negatives of the species in their different stages of development, at successive intervals throughout the season. These constitute a series of illustrations of fishes entirely unequaled; forming an admirable basis for a systematic work upon the food-fishes of the United States, should authority be obtained to prepare and publish it.”

Report, 1876. U. S. Commission of Fish and Fish and Fisheries, Report of the Commissioner for 1873-1875, 3,

p. XIV:

“The results of Professor Verrill’s labors, and those of his associates in the department of marine natural history and plants, will be furnished in a special report; although it may be proper here to state that over one hundred species of invertebrates, new to the fauna of New England, were secured, most of them northern species, and many undescribed.”

Report, 1882. U. S. Commission of Fish and Fish and Fisheries, Report of the Commissioner for 1879, 7, - Background image

Report, 1885. U. S. Commission of Fish and Fish and Fisheries, Report of the Commissioner for 1883, 11, - Fig