150 Years of Woods Hole Science

10

Background image: Site Of Future U.S. Fisheries Commission from Marine Biological Laboratory (Woods Hole, Mass.); Arizona Board of Regents: https://hdl.handle.net/1912/22514

References:

Archives of the Woods Hole Historical Museum, Woods Hole, MA:

Gaines, J. S., 2007. Pacific Guano Company. Spritsail, A Journal of the History of Falmouth and Vicinity, 21(2), Summer 2007, Woods Hole Historical Collection, Woods Hole, MA.

p. 11:

“The company’s roots lie many years earlier in East Dennis, at the Shiverick shipyard. There the Shiverick family, with the backing of the Crowells, captains and owners of the ships and by necessity financiers, built sailing vessels that were sailed all around the world…Unfortunately by the 1850s…The ships often spent months looking for a suitable cargo to carry back to New England. Simultaneously, with the beginning of the industrial age, men were developing methods for more productive agriculture. The nutrients of the soil were seriously depleted from years of poor soil management…For years farmers, had been applying lime to “sweeten” their fields, but this did little to enrich the soil…Farmers could not keep up with the demands of the rapidly growing population. In this brilliant age of invention, men applied their knowledge to the creation of alternate sources for revitalizing the fields.”

pp. 11-12:

“Inquisitive explorers observed that islands along the west coast of South America had guano, hardened and dried bird dung, several hundred feet thick. It had accumulated over thousands of years from nesting colonies of sea-birds. Guano, high in nitrogen and phosphorus nutrients, was tried as a fertilizer, and declared successful, ten times richer than manure. Much less effort was required of the farmer to spread guano on the fields than to spread the equivalent amount of nutrient enrichment from cart-loads of manure. The beginning of the fertilizer industry had come.”

p. 12:

“…the Yankees were quick to see that they might do even better financially if they could own both the guano supply and fertilizer production. The U.S. government stepped in to support the guano industry. In 1856 Congress passed the U.S. Guano Act stating that U.S. citizens could claim any uninhabited guano island in the worls that was not claimed by another country as a U.S. possession, and have exclusive rights to mine guano. The U.S. Navy was directed to back up this claim. Companies could use this protection to explore and claim other islands. This allowed Prince Sears Crowell, ship’s captain, head of the Crowell family of Cape Cod and outspoken abolitionist, to avoid the Peruvian labor practices he abhorred. As an additional bonus, he and other ship owners could guarantee cargo for their clipper ships.”

pp. 12-13:

“The Crowells and Shivericks, joining with the Boston firm of Glidden and Williams, formed the Pacific Guano Company in 1859…They searched Cape Cod for the best spot for their factory, and chose Woods Hole, the only natural deep water harbor. They bought several acres on Long Neck, the peninsula stretching out to the west off the end of Woods Hole. Until then it had been used only for sheep pasture.”

p. 13:

“One of the Crowell sons came to Woods Hole as the company’s chemist, charged with adding improvements to plain guano to make an even more effective fertilizer. One of the Shiverick sons came to be superintendent.”

pp. 14-15:

“The company thrived…As the company grew, so did the town. In 1850 Woods Hole had a population of 200; by 1880 the population had grown to 508, mostly due to the guano company.”

Galtsoff, P.S., 1962. The story of the bureau of commercial fisheries, Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, Massachusetts (Vol. 145). US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Commercial Fisheries.

p. 5:

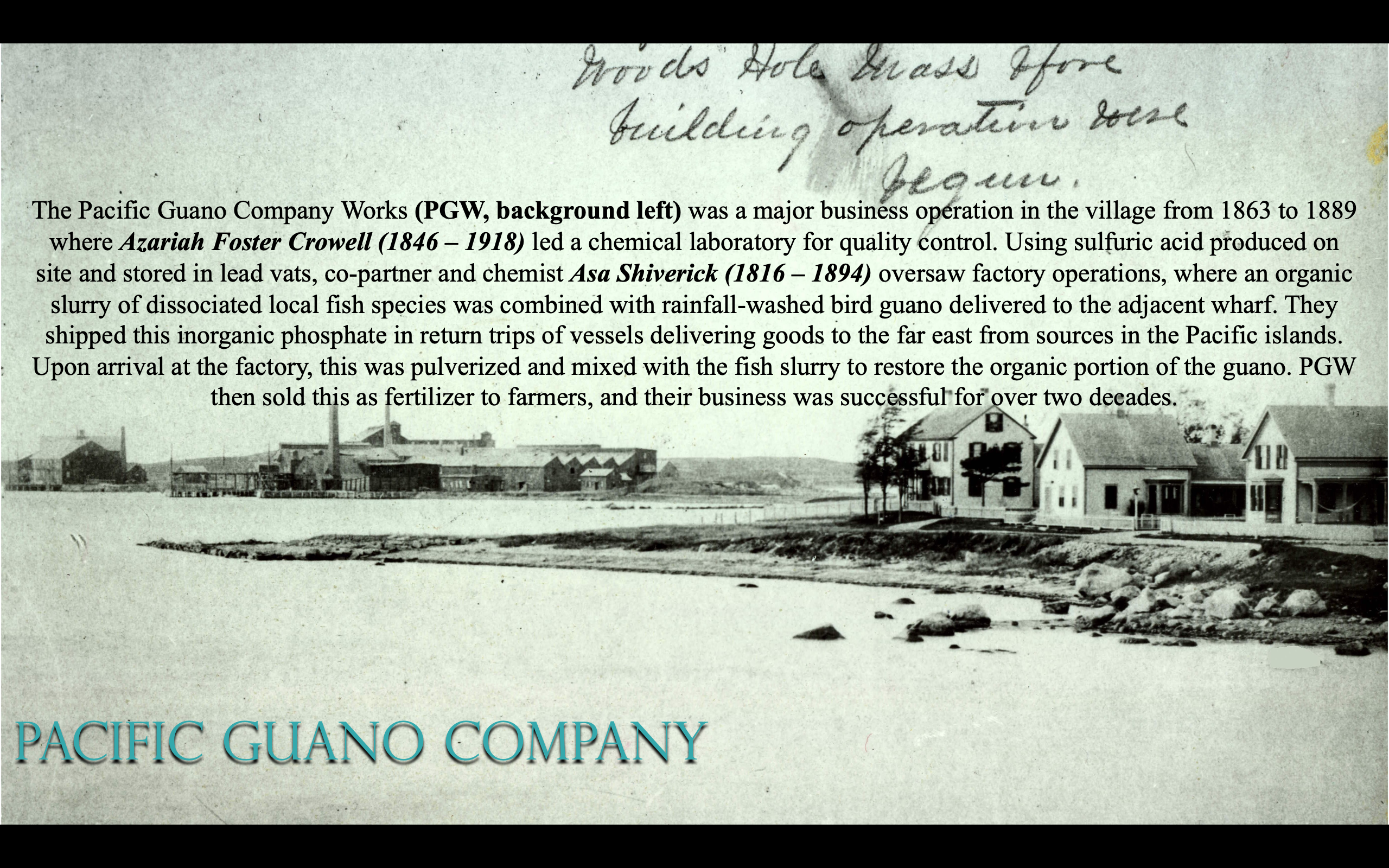

“During the years from 1863 to 1889, when the Pacific Guano Works was in operation, the life of Woods Hole centered around the plant which was built at Long Neck near the entrance to what is known now as Penzance Point... Many large sailing vessels carrying sulphur from Italy, nitrate of soda from Chile, potash from Germany, and many schooners under the American flag loaded with guano and phosphorus from the Pacific Coast of South America were anchored in Great Harbor waiting for their turn to unload their cargoes. The number of laborers regularly employed by the Guano Company varied from 150 to 200 men, mostly Irishmen brought in under contract. Several local fishermen found additional employment as pilots for guano ships.”

p. 6:

“”The Pacific Guano Works was established by the shipping merchants of Boston who were seeking cargo for the return voyage of their ships…The guano deposits of one of the Pacific islands seemed to furnish this opportunity…came into possession and control of Howland Island. This island is located in the middle of the Pacific Ocean…At the same time appropriate plant and docking facilities were built at Woods Hole and 33 large sailing ships became available for hauling guano. Unlike the well-known guano islands off the coast of Peru, Howland Island is located in the zone of abundant rainfall. Consequently, the guano deposits of the island were leached of organic components and consisted of highly concentrated phosphate of lime. Fertilizer produced by the company was made by restoring the lost organic matter of the phosphate rock by adding the right proportion of organic constituents which were obtained from menhaden, pogy, and other industrial fish which abound in Cape Cod waters. The rock was pulverized and purified by washing; fish brought in by local fishermen were first pressed to extract oil, and the residue digested with sulphuric acid, washed, and dried. Acid was produced locally from sulphur imported from Sicily, and the digestion of fish flesh was carried out in large lead-lined vats. The plant was well equipped with machinery needed for the process and even had a chemical laboratory where chemists made the necessary analyses.”

p. 7:

“While the scientists, agriculturalists, and stockholders of the company thought very highly of the guano works, the existence of a malodorous plant was not appreciated by the residents of Woods Hole who suffered from a strongly offensive odor whenever the wind was from the west. Woods Hole Might have continued to grow as one of the factory towns of Massachusetts but, fortunately for the progress of science and good fortune of its residents (except those who invested their savings in the shares of Pacific Guano Works), the company began to decline and became bankrupt in 1889.”